THE HISTORICAL RESISTANCE OF LATIN AMERICA’S FEMINIST MOVEMENTS

Widely known as the International Women’s Day, March 8th is one of the most important dates for Latin American women. During the past years, they have taken over cities across the continent to advocate for their lives and rights, and to denounce endemic gender-based violence from the southernmost part of Argentina to the Mexican borders with the United States.

The unusual magnitude of women’s mobilization in this hemisphere is not by chance. More than sharing a common history, Latin American women also face common hardships stemming from widespread misogynist societies and sexual violence, still widely accepted in this continent. As reported by the United Nations, this region is accounted as the most dangerous for women worldwide. Unsurprisingly, many Latin American countries are among those with the highest femicide rates in the world, of which the greatest majority remains unpunished. When it comes to sexual and reproductive rights, it’s still this region where are located the countries with the most restrictive abortion laws. Meanwhile, the UN also reports Latin American numbers of teenage pregnancy as the second highest in the world.

While some societies take for granted many legal guarantees that protect women’s rights, present-day Latin American women face the difficult task of resisting and surviving in the deadliest region in the world. Where simply being a woman can mean being at risk of murder, raising their voice against their condition is truly revolutionary.

Different from what some might expect, Latin American women have long been fighting for their rights, despite the highly violent and repressive circumstances. In the 60s and 70s, the outbreak of military dictatorships around this continent triggered many feminist movements in Latin America to gain force. As mentioned by the journal Feminisms in Latin America, not only they challenged patriarchal foundations but also actively engaged in opposition movements against authoritarian regimes.

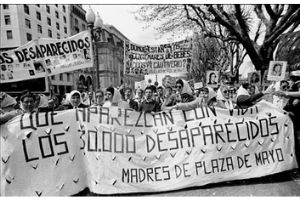

Similarly to places like North America and Europe during these decades, in Latin America too feminist mobilizations began as a wave of protests against women’s historical condition. The particularity of the latter, however, was the primary focus on opposing the regimes’ systematic persecution, torture and forced disappearance of those considered subversive to national security. This also gave birth to long-term movements including searching for missing relatives, as in the Madres of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina.

Similarly to places like North America and Europe during these decades, in Latin America too feminist mobilizations began as a wave of protests against women’s historical condition. The particularity of the latter, however, was the primary focus on opposing the regimes’ systematic persecution, torture and forced disappearance of those considered subversive to national security. This also gave birth to long-term movements including searching for missing relatives, as in the Madres of Plaza de Mayo in Argentina.

As revealed by the dictatorship archives in Brazil, many women also actively engaged in armed guerrilla and clandestine organizations. They were considered double transgressors: first, for contesting the authoritarian ruling order; and second, for rejecting their roles of mothers and housewives, as was expected by highly conservative societies in Latin America.

While widespread feminist discussions centered on sexuality and the body’s autonomy were so important abroad, in Latin America, they were considered secondary to major sectors of the Left. For many of those drawing from Guevarist and Leninist principles, class struggle, redemocratization and revolutionary ideals were prioritized over gender for years.

In Argentina, for example, a former militant reported that the feminist demand was seen as less important than building a new socialist society, in which women’s rights would come automatically as a consequence. In Chile, dictatorship archives reveal that the feminist movement originally emerged to fight for democracy, and later, address demands to end gender discrimination. However, internal clashes between those considered “feminist” and “politicians” started rising in the end of the military regime. During the 90s, as reported by Unifem, three out of five countries in Central America attribute their political stability to successful negotiations brought about by women.

Notwithstanding this recurrent conflict between gender issues and politics, the singularity of the continent’s authoritarian environment, economic dependence and political repression highly contributed to the uniqueness of feminist political projects in this part of the world. This was because they emerged from the intersection between gender oppression and other forms of exploitation practiced by dictatorial regimes.

As years passed, militants started to prioritize a political and social agenda to address the historical condition of women’s subordination, questioning left wing revolutionary groups’ tendency to postpone these discussions to give space to class struggle. At the same time, increasing urbanization led to the feminist movement’s expansion to cities’ peripheries. This helped to better address conditions of poor, working-class and peasant women, who suffered the most from Latin America’s economic inequalities. Such social environment gave birth to a series of meetings across the continent dedicated entirely to discussing feminist issues, the so-called Encuentros Feministas de America Latina. Since 1981, they have been ongoing every two or three years.

As years passed, militants started to prioritize a political and social agenda to address the historical condition of women’s subordination, questioning left wing revolutionary groups’ tendency to postpone these discussions to give space to class struggle. At the same time, increasing urbanization led to the feminist movement’s expansion to cities’ peripheries. This helped to better address conditions of poor, working-class and peasant women, who suffered the most from Latin America’s economic inequalities. Such social environment gave birth to a series of meetings across the continent dedicated entirely to discussing feminist issues, the so-called Encuentros Feministas de America Latina. Since 1981, they have been ongoing every two or three years.

These meetings have become spaces for debate, growth and also conflict among a wide variety of voices and political positions among women. This was also when the feminist label was reclaimed by many working-class, black, indigenous, migrant, previously exiled and lesbian women – who refused to accept the idea of gender oppression as just another form of colonialism. Instead, the movement has developed their own agenda and identity based on a gendered gaze of society, politics and culture, distinct from that of the male-dominated revolutionary Left. Additionally, their decolonial perspective based on criticism towards militarism, neoliberalism and the capitalist system has remained a unique feature of the Latin American feminist movement.

Thanks to these initiatives, the number of feminist magazines, film and video contents, centers for victims of gender-based violence, feminist health collectives, lesbian rights groups, and other feminist projects have spread across the continent. Around the same time, in 1975 the United Nations also organized the first world conference on the status of women in Mexico, which coincided with International Women’s Year.

Despite having achieved so much over the past decades, women in Latin America still face innumerable hardships. This is especially true for minorities like women of color, those in poverty and LGBTQIAP+ people, who are particularly affected by a patriarchal, highly unequal and violent environment such as the one in Latin America. These conditions are particularly aggravated by the rise of a recent conservative wave in the continent, threatening to tear apart the few achievements women have made in these years. However, just like history has shown, women in Latin America are not easily intimidated by overwhelming political conditions. As we remember our history, the importance of feminism has never been so evident: thanks to its legacy, we will now protest for more.

Cover image from: memoriasdaditadura.org.br

Italian version here: lafalla.cassero.it/oltre-l8-marzo

Perseguitaci