IN A DYSTOPIAN WORLD, DO WE HAVE THE POWER OF RESISTANCE?

Utopian novels written by women have developed greatly across the 20th century.

While Thomas More’s Utopia has been repeatedly reinvented across time, utopian novels seemed to have disappeared after the Second World War. They re-emerged in the 1970s, when feminist science-fiction gave new birth to the genre. However, something was different in these writings. Gender issues, women’s subjectivity, reproduction and sexuality became the stories’ core, and inaugurated the so-called “critical utopias”. Despite being a powerful form of resistance, this literary genre was short-lived.

As Raffaella Baccolini, Professor of Intercultural and Gender Studies at the University of Bologna and co-director of the “Ralahine Utopian Studies” publishing project, points out, critical dystopias started growing predominantly amid feminist authors towards the end of the century. Unlike previous times, this new genre didn’t treat utopia and dystopia as mutually exclusive and static. Instead, it offered novels ambiguous and open endings, where not only resistance was possible but also the impulse to transform society.

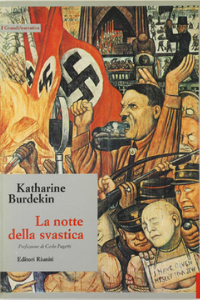

However, it was back in 1937 when Katharine Burdekin’s Swastika Night became probably the first-ever written critical dystopia. Published under the pseudonym of Murray Constantine, Burdekin’s novel goes further beyond, denouncing Germany’s totalitarian Nazi regime and predicting many of the atrocities of the impending war. Unlike many male authors who later followed Burdekin without taking notice of gender politics, she turns to womens’ submission and oppression to explain how totalitarian and patriarchal regimes are founded. Building on this, Swastika Night depicts the construction of female inferiority and the cult of masculinity as far from being anomalies of fascist regimes. Rather, they are only quantitatively different from our current realities based on gender roles.

Portraying a German empire built hundreds of years after the Second World War, the novel reveals a dystopian society built by men to benefit their own needs. There, women are deprived of all rights, being confined in cages excluded from male society. Living in a state of apathy and ignorance, they lack identities, agency of their own bodies, and their own subjectivity. As a result of their inferiority, they serve solely to a biological purpose of procreation, and must give their sons away to the empire shortly after giving birth.

Portraying a German empire built hundreds of years after the Second World War, the novel reveals a dystopian society built by men to benefit their own needs. There, women are deprived of all rights, being confined in cages excluded from male society. Living in a state of apathy and ignorance, they lack identities, agency of their own bodies, and their own subjectivity. As a result of their inferiority, they serve solely to a biological purpose of procreation, and must give their sons away to the empire shortly after giving birth.

Little is known about the antecedents of this regime, and little is questioned by those who belong to the Nazi empire. All the evidence from its historical past has been destroyed: books, literature writings, or any information about previous foreign regimes. Memories have been replaced by a hegemonic discourse, based on a cult of oppression and violence. Language only serves to guarantee the repetition of norms, taken for granted in the attitudes of both men and women. Yet, there is still room for resistance.

The truth about the regime’s main foundations and history has been well hidden. As a family secret and against the regime’s rules, they are kept in a book written by Knight von Hess, and preserved over generations. With his writings, an old photograph has also been passed down to the family’s last knight in power. When the latter decides to share the secret with Alfred, an Englishman he feels close to, the resistance driver emerges against the totalitarian Nazi regime.

Through long conversations with the Knight, Alfred becomes aware of all the lies that constitute the regime’s structure. Above all, he is particularly struck by one: the reduction of women as a natural, innate phenomenon. Rather than biological, women’s inferiority is, in fact, a gendered construction that a patriarchal system has long relied on to support its totalitarian regime. Alfred concludes women have been deprived of two things men have always had. First, the right of rejection, which led to sexual vulnerability. Secondly, the lack of pride in their gender, which prevented them from recognizing the fallacy of their inferiority. Consequently, women have been absent from being subjects themselves, and have become the projection of male creation, in a world guided by values of masculinity.

After discovering this counter-narrative against the regime’s manipulated history, Alfred starts becoming attached to his newborn daughter, Edith. His desire to make his daughter a fully realized individual, as an impossible wish, brings to light an important facet of the novel: the constant dichotomy between an emerging defiance potential against the regime, and the only power to do so held by a man.

While this could seem contradictory for a feminist novel, Burdekin seems to have often highlighted the ambiguous nature of critical dystopias. As Baccolini explains in her contribution to the collection of critical essays Future Females, The Next Generation, it is true that Alfred has decided not to provide agency for his daughter, in order to keep her from being excluded by other women. However, his choice to pass the book and its principles onto his son guaranteed that his true beliefs would live on. In other words, the ability to keep a counter-memory alive in a regime that doesn’t tolerate other narratives than its own is already, per se, a subversive act – perhaps the only one possible in that context.

It is striking how contemporary Swastika Night still is, despite having been written over 70 years ago. The totalitarian regime depicted in this science-fiction book is, after all, not so radically different from our world. Already in the pre-war period, Burdekin showed us what’s at stake if we don’t seriously hold authoritarian regimes accountable for past violations, and for current acts of violence. She points out the importance of memory studies as a way to prevent the repetition of history and to challenge social order, which is, in fact, constructed.

It is striking how contemporary Swastika Night still is, despite having been written over 70 years ago. The totalitarian regime depicted in this science-fiction book is, after all, not so radically different from our world. Already in the pre-war period, Burdekin showed us what’s at stake if we don’t seriously hold authoritarian regimes accountable for past violations, and for current acts of violence. She points out the importance of memory studies as a way to prevent the repetition of history and to challenge social order, which is, in fact, constructed.

Central to this is Burdekin’s powerful criticism against the regime’s ideology that determined the status of inferiority and submission of women as “natural”, rather than a culturally imposed fabrication. As also posed by Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, being a woman has been historically constructed to reflect the figure of men, rather than their own subjectivity. By deconstructing gender and hegemonic discourse, the author also speaks to our present reality, many years later.

Burdekin’s struggle to denounce women’s inferiority as part of a dominant narrative is probably the book’s greatest contribution to future societies. By defying the classical dystopian genre, the novel’s open ending addresses the possibility of change that can exist, in all of our worlds – if we dare to resist.

Il presente articolo è disponibile anche tradotto in italiano

Perseguitaci